“School Lunches Suck”

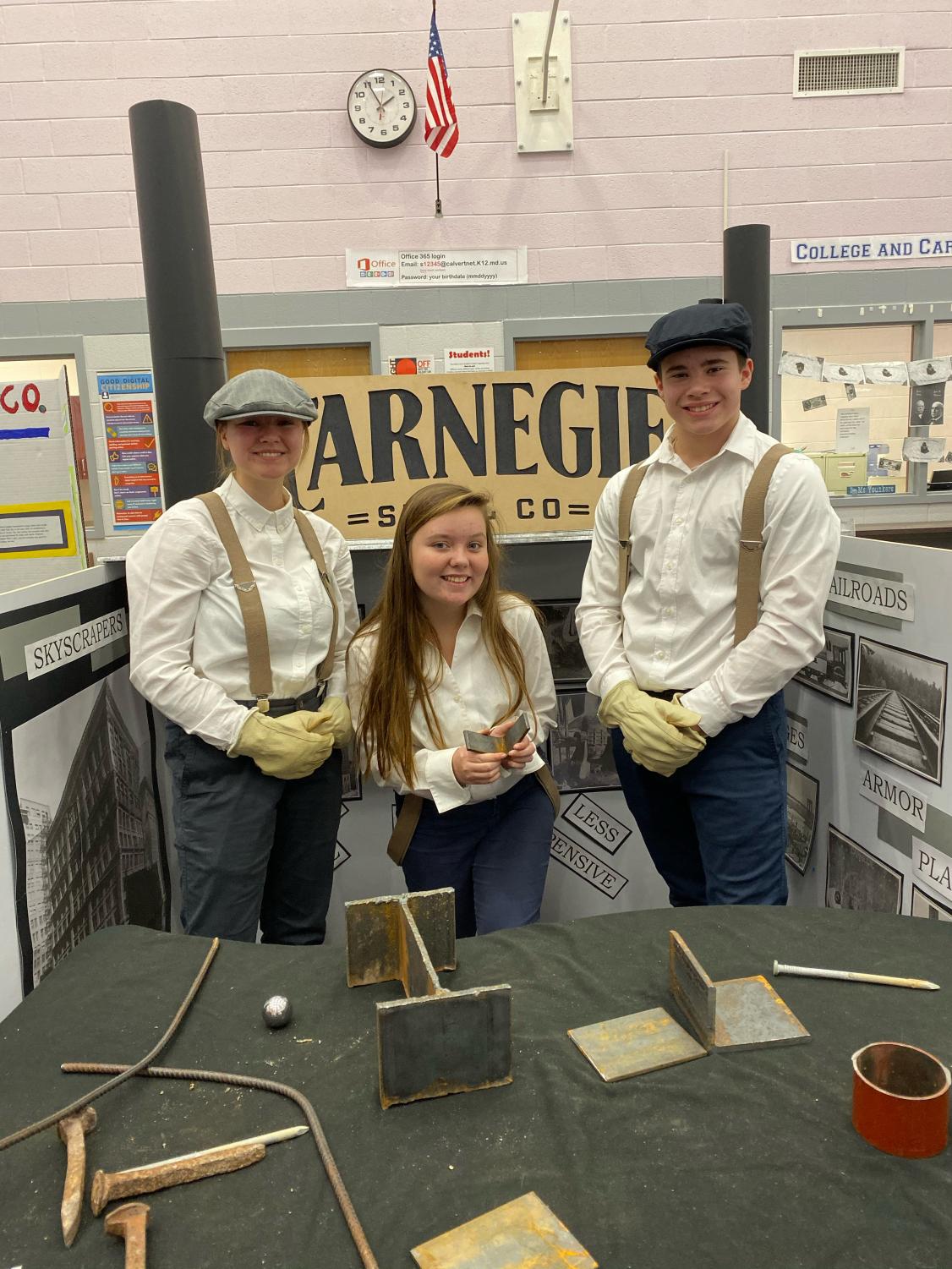

Students in the middle of the A Lunch-rush, all having arrived within about one minute of each other.

November 29, 2021

The Unknown Story Behind Your Free Lunches

Student Opinion

Fourth period is crawling to a close and stomachs are grumbling. Over half of the school is planning their quickest route to the lunchroom. When the lunch bell rings, it is only seconds before the hallways and stairwells flood with more than five hundred kids attempting to be the first in line. They shove their way through the cafeteria doors, the crowd finally finding its lull as the stationary lunch lines grow in number. The progression of the line, which is made up of hundreds of students, is dependent upon five cafeteria workers that are serving today’s lunch in a blur. The frenzy is a product of one crucial development: this year, school lunches are free.

The new United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) waiver for free school lunches for the current 2021—2022 school year has evoked a plethora of opinions from Huntingtown High School’s student body. Many claim that the quality of the school’s lunches has decreased from previous years’, alongside their price, and a majority are feeling both hungry and disappointed.

“The USDA answered the call to help America’s schools and childcare institutions serve high-quality meals… as children safely return to their regular routines,” reads the 2021 USDA press release. This new funding stems from President Biden’s plan to make the return to public schools safe and convenient for those who suffered great losses from COVID-19. The USDA claims it’s a “win-win for parents and students.” Though the waiver seems ideal in theory, how many of Huntingtown’s students are feeling like winners?

“There’s hardly any quality,” remarks a Huntingtown senior, who feels as though the variety and excellence of the meals is lacking. “Sometimes it feels like I’m eating the same thing every day.”

“The quality honestly depends on the day,” disagrees a junior who has been taking school lunches since their freshman year. “When they serve chicken nuggets, the portions are usually really small, so I’m still feeling hungry after. But other meals like the pulled pork are a lot more filling.”

Another senior thinks the general dissatisfaction regarding the school’s lunches is a mere result of the collective consciousness of the student body. “If one person says they don’t like the school food, no one is going to disagree with them and defend it. The opinion will spread.” Similarly, it is a widely regarded stereotype outside of Calvert County that “school lunches suck,” and going against this popularly cherished belief would result in some sort of ostracism. Regardless, this individual feels it is a good program that many students are publicly disregarding in order to fit in.

Though none of these interviewees depend on free lunches due to their financial status, they still decide to take advantage of it every day. “I mean, it’s free,” says a school lunch regular. “And I guess I could bring my own lunch, but I’m a busy [senior] with a job, AP classes, after-school activities, and I don’t get a lot of sleep. I don’t really have time to throw together a lunch every day and still make it to school on time.” It all comes down to convenience. And if standing in a lunch line for ten to fifteen minutes for a free lunch ultimately saves more time, many are willing to make that decision.

Generally, however, students continue to claim that they still feel hungry after finishing their lunches. A common complaint relates to the discrepancies in portion sizes. “[They’re] usually really small,” says another regular. “I’m never really full after lunch.” They say this makes it hard for them to focus or do well in school with hunger pains, which is a great concern of the lunch staff.

Staff Perspective

But what goes on behind the scenes is a different story, where a small team of our dedicated mealtime staff is working tirelessly around the clock to provide students with free lunches. This new waiver for all K-12 Maryland schools has transformed their preparation and serving experience into a far more overwhelming environment. “It’s a guessing game,” explains Gale O’Dell, the Cafeteria Manager. They never know the exact number of students who will be having school lunch each day, so estimations on how many meals to prepare must always be made. Regardless, they still ensure that every student meets the government’s nutritional requirements daily and that no student is turned away without food.

Furthermore, the lunch staff is terribly undermanned. In a kitchen that requires at least seven employees, there are only three permanent workers. Depending on the number of subs they have in a day, their staff can gain up to five or six employees. But rarely does this happen as O’Dell says that “subs are very few and far between.” She continues to explain that more subs could ultimately hinder the food preparation process, as much of the time they spend on preparing the food would have to be replaced with showing them the ropes of their kitchen, due to the different layouts of kitchens across the counties. It is vital that this development is understood by the student body when complaints about the wait time arise.

“We’re kind of like the bus drivers, except we’re in the building,” says O’Dell, referring to the recent Calvert County bus strike that occurred due to issues regarding lack of staff and pay. There has been an unrecognized county-wide shortage of mealtime staff since well before the pandemic. It is difficult for a kitchen to run efficiently without the proper staff required for serving and preparing the meals, which not only stresses out the employees but also makes the serving process inefficient and somewhat chaotic.

In response to the lack of variety, O’Dell provided a written statement with the following: “Our options are extremely limited as compared to previous years because the demand for food has increased, and the available supplies are limited. This means we aren’t able to offer some of the favorite items we have offered in the past, and for that, I do apologize. It is disappointing for us, and I’m sure it is disappointing for the students as well.” However, O’Dell remains hopeful that these items will be incorporated into the menu at some point, although it is unknown when that will be.

It may be instinctual to blame the school itself for the perceived small portion sizes or lack of quality. But it must be recognized that these criticisms are not a reflection of the school itself, nor the dedicated staff who work to feed half the school daily. This is a call to their distributor, Dori Foods, a Wholesale Food Distributor located in Richmond, Virginia. O’Dell reveals that there have been some recent delivery problems, and multiple online reviews from previous employees suggest having had similar issues when working with the company. A one-star review from December 22, 2019, reads, “Mismanaged and inventory miscalculated and needs organization.” Another one-star review from April 4, 2019, also claims that there is, “poor management, low pay, and terrible training… this is a toxic place to work.” Distribution discrepancies have been a large reason why there has been a shortage of available food offered, which must also be taken into consideration when the quality and quantity of the food seem lacking.

In addition to this, all Maryland public schools are self-supporting programs when it comes to providing free school lunches. This means they are expected to generate enough revenue to cover everything within the program from food, labor, equipment, health insurance, trash removal, paper goods, etc. All programs typically operate on an extremely tight budget, prompting them to participate in cooperative purchasing programs with other counties to increase their buying power and “make the most of every dollar.” With every free lunch provided, the government reimburses the school $4.31, which has increased about a dollar since previous years but is ultimately an infinitesimal amount. Essentially, funding is scarce, resources are dwindling, and all the while Huntingtown’s lunch staff is expected to generate enough money for their own salaries.

Saying everything is different this year would be a grotesque understatement. Apart from schoolwide Covid regulations, mask mandates, and almost exclusively virtual assignments, it is imperative to understand the toll this free lunch waiver has had on workers and the quality of food alike. “For the kids’ sake, I’m very glad it’s free,” says O’Dell. But she’s heartbroken that some students may still feel hungry after leaving the lunchroom, or that they’re not receiving the quality of food that they’re used to.

In past years, lunch workers have paid out of their own pocket for certain hungry students to feel full. But for students who are financially able, she encourages them to take full advantage of every free option offered by the school. If that remains insufficient, though, then students are further encouraged to buy an extra meal or sides. There is only so much the school can provide with the free food waiver, which many falsely believe alludes to free, unlimited resources. However, this is simply not the case.

Regardless of if “school lunches suck” or not, which is entirely based on opinion, this deeper understanding and perspective surrounding the reasons for these changes is essential as our free lunches involve a lot more than a cafeteria worker merely handing us a slice of pizza.