Chaos: The Bus Driver Strike

From one day to the next, buses evaporated from our lives. Photo by Jennifer Izaguirre.

November 29, 2021

A shrill, intrusive alarm rings in your ear, jolting you awake. Time to go to school! Sluggishly, you get out of bed, get dressed, and gulp down your breakfast. But where is the school bus? The day is Monday, October 11, 2021, and your bus never came to pick you up. The cause? A bus driver strike that devastated Calvert County schools.

Eight different Calvert County schools were affected by the strike on October 11th, marking the beginning of a series of demonstrations organized by Calvert County bus drivers. The first demonstration was merely a “sick out,” a day when most absentee bus drivers called in sick, leaving the school system without twenty-two buses. However, as time wore on and bus drivers’ demands were not addressed, protests grew bolder and more organized. By Wednesday, October 13th, bus drivers were officially on strike and had announced that they would continue to strike for up to 10 days. Only 40 out of 134 buses ran their normal routes that morning.

The Grievances and Their Causes

The strike was the bus drivers’ plea for improved working conditions. In 2021, they faced low salaries, diminishing work benefits, and inequity in routes. So, something had to change.

Demand for Higher Pay

Bus drivers were only guaranteed a workday of at least five and three-quarter hours with a starting rate of just $18.01. Taking into account that they work for 180 days of school in the year, their annual salary is just over $18,000 before taxes. Mrs. Bowie Little-Downs, bus driver and co-owner of Downs & Downs school bus contracting, explains that drivers were particularly vulnerable during the pandemic “quite simply because they’re underpaid.” Sadly, she’s witnessed “drivers who’ve been foreclosed on, even during the moratorium, when it wasn’t to happen… We’ve had drivers, who’ve been evicted from their homes or apartments.”

At first glance, one might be inclined to blame the bus contractors. After all, school bus drivers are not school system employees. Rather, they work for contractors, like Mrs. Little Downs. However, when asked who sets bus driver wages, Mrs. Little-Downs revealed that Calvert County Public Schools (CCPS) determines the pay for drivers. “Calvert County Public Schools tells us, this is what we will give you [the contractors].” In effect, bus drivers are paid by the contractors. Yet, the school system is responsible for paying contractors a guaranteed wage for their drivers. So, this intriguing payment system requires accountability from both parties. Moreover, Mrs. Little-Downs even shed light on procedures for salary raises, describing that pay changes go through CCPS. “The raises that they approve for us are never in keeping with the inflation rate. We’ve had instances where we’ve gotten half of a percent… we’re talking a 15 cent raise or 75 cents, not even a dollar raise.”

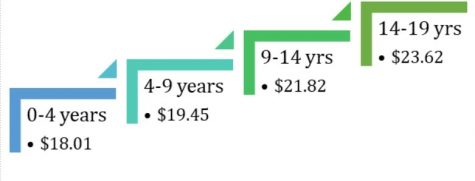

Bus drivers are paid via a system involving steps. Each subsequent step has a pay increase. However, you can only move up a step once you have been working for a certain number of years. For instance, once a driver has worked for over 14 years, they ascend to the final step and earn the highest amount possible: $23.62. Regrettably, this means that the pay raises cease after you attain over 14 years of experience. The result, as Mrs. Little-Downs puts it, is that “somebody who has been driving 19 years is making the same amount of money as somebody who’s then driving 32 years.” Thus, many drivers grew frustrated by the lack of compensation despite their years-long dedication to the profession.

Note: This step system was altered after the strike. See The New Agreement section for details.

Diminishing Work Benefits

In terms of work benefits, bus drivers lost a crucial aspect of their plan: life insurance. For each school bus contractor that the school system works with, CCPS pays a sum that goes towards bus drivers’ benefits. However, the funding provided for those fringe benefits has decreased. So, as the premium for bus drivers’ life insurance rose this year, it could no longer be afforded and was completely cut. What was meant to be a lump sum, CCPS’s cash infusion for the benefit trust, was instead broken down to $300 per contract. The reasoning was that CCPS withheld amounts corresponding to buses that have no driver. Sadly, decreased funding because of the driver shortage contributes to the driver shortage. Mrs. Little-Downs explains that one of the incentives to become a driver is the benefit package, so altering it “is part of the reason why we have no drivers… They’re just ripping the rug out from under their feet.”

The benefits that the bus drivers have been able to retain include medical, dental, and vision insurance.

Inequity In Routes

The bus driver shortage has affected the workday of the average bus driver. “Some drivers are doing the work of multiple buses,” exclaims Mrs. Little-Downs. According to her, they may be facing an eleven or twelve-hour day. Whereas, other drivers only have a five and three-quarter day, the minimum. So, some are overworked, and others are barely making a living wage. To resolve the inequity, CCPS has instructed contractors to redistribute work among drivers. However, “anybody who is lucky enough to get an 11 [or] 12-hour day is not giving up their hours… those longer routes are few and far between. Everyone wants them,” stresses Mrs. Little-Downs. Making matters worse, bus drivers are not paid overtime. “They’re getting paid for nine hours straight, not time and a half for anything over eight.”

The Driver Shortage

While factors like pay and diminishing benefits have certainly contributed to the driver shortage, the lack of drivers is not a new issue. In fact, the availability of drivers has been decreasing for about a decade.

This is partly due to new requirements for becoming a bus driver. Notably, Calvert County requires that bus drivers pass a DOT (Department of Transportation) physical every year. If a driver does not pass the exam, then they may be temporarily or permanently disqualified from driving in the county. The official term for this is a medical DQ (disqualification). Furthermore, the physical itself has been altered. Now, there is more scrutiny about sleep apnea, a disorder where an individual stops breathing while they sleep. To determine whether a prospective bus driver has sleep apnea, the neck size of the driver is obtained. As, a circumference greater than 19 inches is an indicator of sleep apnea. Similarly, individuals are surveyed to determine if they snore, as that is also a sign of the disorder. Sadly, Mrs. Little-Downs fears that although it is possible that the prospective driver has sleep apnea because they snore, “it’s also possible that they’ve got a stuffy nose or a cold.”

The additional examinations for sleep apnea come from federal requirements initially intended for truck drivers. Truck drivers were falling asleep behind the wheel, so the federal government sought to prevent car accidents by monitoring who had sleep apnea among the drivers with long, overnight hauls. Despite this intended audience, however, the changes were also blanketed over bus drivers, which inadvertently served to knock a lot of prospective employees.

Yet another factor contributing to the shortage is the concern of COVID-19. School bus drivers include retirees that are more vulnerable amidst new variants. So, some left to safeguard their health. You can’t blame these individuals, but losing their contribution as drivers is certainly being felt. As shown by the inequity in routes, the driver shortage put more pressure on our drivers while they were feeling undervalued. So, it was only a matter of time before a strike erupted.

The Strike’s Effects on Huntingtown High

At Huntingtown, the bus driver strike affected everyone. “It got to a point where we were only getting maybe about eight buses in the morning time,” explains Mr. Butler. So, the majority of students had to be dropped off at the school. To the frustration of many, this meant that Route 4 became heavily congested. Even students who drove to school had to sit in traffic. Thankfully, our school was able to adapt. Mr. Butler explains that to facilitate the flow of traffic, the few buses that would arrive each morning were told to drop students off immediately and leave right after. In this way, space could be freed up in the front parking lot so cars dropping students off could be funneled in.

Then, once students were finally able to arrive at school, many schedules were disrupted. Not only was first period cut short several days in a row because of morning delays, but CTA students were also left without buses to take them to Calvert High. So, they were sent to Huntingtown’s cafeteria, where they were to join their classes virtually on Teams. This left many students frustrated because they were stuck staring at a screen when they were looking forward to the hands-on instruction that is characteristic of CTA.

Parents and guardians were also heavily impacted by the strike. Many were forced to dedicate time in the morning to drop their students off at school, which meant sitting in traffic and even being late to work. “Calvert County has a lot of families, parent/guardians who leave the county early in the morning time, and they rely on the buses to be there for the kids… buses are essential for the community,” notes Mr. Butler.

So, the strike had its desired effect: it drew our attention to the importance of bus drivers. We realized how valuable they were only after they were gone, when it affected our schedules, education, and work. Whereas, beforehand, some of us may have failed to truly see our drivers. Mrs. Little-Downs explains how this felt, “We greet our kids. Most, every driver will say, good morning and have a good day, or see you tomorrow… And it is just disheartening at times to have students just walk by us and not acknowledge us… I mean, it just compounds what the school system is doing to us.”

Bus drivers have the responsibility of looking after kids as they take them to school, as well as returning them home safely each day. They make parents’ lives easier, and they support our school community. When they were gone things fell apart. So, the next time you see a driver, really see them. Even a simple good morning can make their day.

The Drivers that Did Not Strike

The few buses that were still running during the strike were primarily driven by contractors. However, this was not a sign of disunity. On the contrary, it was done out of necessity. Some contractors, like Mrs. Little-Downs, were unable to strike because they could lose their contracts with CCPS. Mrs. Little Downs explains, “[CCPS] can pluck [bus drivers] from us and erode our business if we were to strike with our drivers.” Nonetheless, Mrs. Little-Downs wholeheartedly supports her employees, “They are the backbone of our business. Without them our buses don’t move… they need this, and they should get it.”

The New Agreement

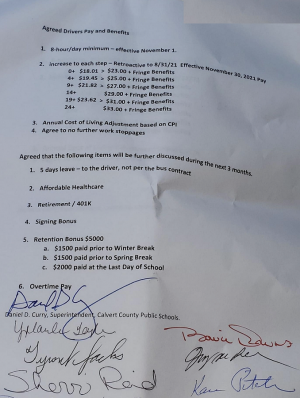

On October 29th, CCPS met with Calvert County bus drivers, contractors, and county government officials to address bus drivers’ demands. In exchange for an agreement to end the bus driver strike, bus drivers are now guaranteed an 8-hour workday and pay increases.

Currently, the starting rate for a bus driver is $23, a $4.99 difference from the previous $18.01 minimum. Also, two additional steps were added to the step payment system. The highest a bus driver can earn is now $33 when they have been working for over 24 years. This agreement has a $2.6 million price tag, and it is truly a testament to the importance of bus drivers in our community.

See the image below for an overview of the agreement signed by Dr. Curry.

Thankfully, this accord signifies renewed stability for schools as bus drivers return to work. “All the buses are here now, they’re here on time. You know, the bus drivers seem happy,” Mr. Butler reassures.

Despite being at the forefront of the effort to mitigate the effects of the strike on Huntingtown, Mr. Butler can sympathize with the drivers, “What they did obviously was effective, but at the expense of parents needing to address their schedules in the morning time to accommodate their students. It’s a tough line to draw. But they had gotten to that point where enough is enough: We need to make a stand and the only way we can do that is to say, ‘we can’t transport until we get what we need.’”

Prior to this agreement, while the strike was still impacting her company, Mrs. Little-Downs asserted, “I want to see my drivers get what they need… it’s long, long overdue, and it is so deserved.” Although issues like affordable healthcare and retirement plans for bus drivers still need to be addressed, this plan is certainly a step in the right direction.